Encouraged by the authors of the website dedicated to Józef Koffler, in this essay I focus first and foremost on the various links between that composer and the city of Vienna. I have quickly realised that, for obvious reasons, the Koffler puzzle contains many lost or unknown pieces. It is hard to predict how much time it will take to bridge the gaps in our knowledge and uncover the facts. The Viennese period of Koffler’s life is partly covered by documents already known to us, to which new materials have been, and will constantly be added.

He also took up short-time jobs. Despite the ongoing military campaigns, the city was vibrant with life and artistic activity. When the war ended and the young, humiliated Republic of Austria made its painful first steps, Vienna’s rich cultural traditions and broadly conceived cultural activity, including musical life, continued to be cultivated without interruption, despite the poverty and creeping inflation[1]. Musical life was not limited to the avant-garde – though the latter would soon (in the late 1920s) become the veritable foundation of Koffler’s life creed. Koffler himself claimed in the essay ‘Drei Begegnungen’, printed in Musikblätter des Anbruch (Arnold Schönberg zum 60. Geburtstag, Vienna 1934) that he had read the harmony handbook (Harmonielehre) written by his would-be demiurge Arnold Schönberg already as a teenager back in Stryj, in the year 1912. Two years later, as a fresh secondary school graduate, he came to the capital on the Danube in order to take up studies.

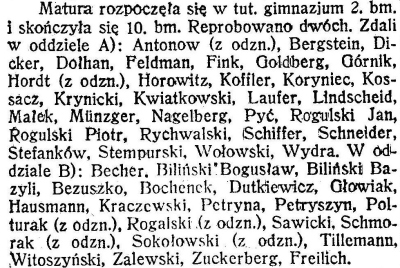

on the end-of-school exams that had taken place in Stryj Gymnasium (secondary school) between 2 and 10 June. Koffler is listed among the several dozen students that passed those exams. This, by the way, is the earliest preserved piece of information about the would-be composer that has been found at the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Austrian National Library).

Barely several weeks passed between the graduation certificate awarding ceremony and the outbreak of World War I (on 28 July). Events on the war front and the Russian army’s September offensive led to a mass flight of Galicia’s inhabitants (several hundred thousand people), including those from Koffler’s hometown, mainly to Vienna. In the column ‘From the Occupied Territories’, the press reported in September 1914:

Stryj was abandoned by its authorities and the Austrian army three days before the Russians entered the town. It was pillaged by the mob but saved from the fires and ravages of war.

(Kurier Lwowski 399 (1914), 2).

When exactly the Koffler family and the 18-year-old Józef himself made up their minds to choose studies Vienna – we do not know. They were well-off and could afford their son’s studies as well as decent lodgings. It is uncertain, however, when and how Józef reached Vienna in 1914 in order to take up studies at the city’s university.[2]

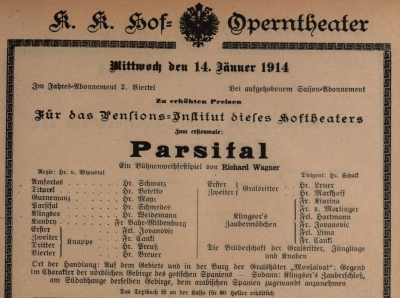

One clue concerning 1914 can be found in Koffler’s reply to Muzyka journal’s questionnaire (8/9 (1935), p. 133), to a question concerning the most important musical and spiritual experiences of his life. Koffler lists two musical works, one of which was a production of Richard Wagner’s opera Parsifal, which he saw at Vienna’s k.k. Hof-Operntheater (Imperial-Royal Court Opera), in the eighteenth year of his life.[3]

that could rightly win young Koffler’s admiration. The well-known critic Karl Lafite reported in the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung (10730, p. 4):

The auditorium was filled to the brim with people listening in complete silence (a thing not to be underestimated) and following all the stages of this work (which places high demands also on the audience) with genuine excitement. It was only before the curtain fell for the last time that a grateful applause was ventured.

Notably, Koffler went to see this production as many as nineteen times (most likely sharing the excitement that was mentioned in the review), which means he continued to go to spectacles also in 1915.

In the same year, on March 18, Koffler appeared before the Austrian Imperial Army's conscription commission and was declared unfit for military service (Doc. BKA-KA - Oesta-Kriegsarchiv. Reference 1464). Tracing what became of him during the First World War years, however, requires further archival research in the Austrian Kriegsarchiv as well as Ukrainian and American archives.

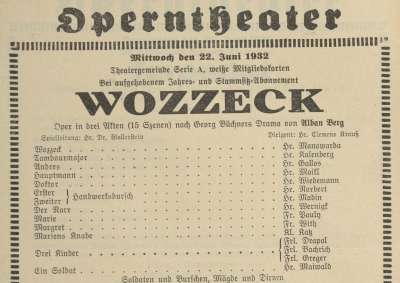

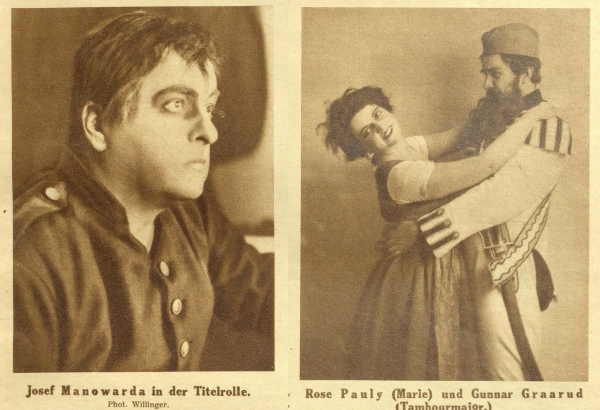

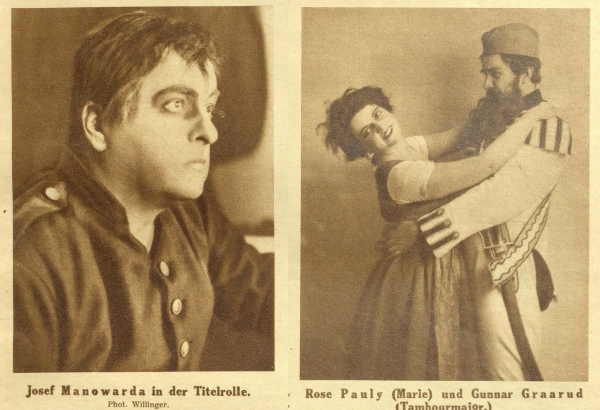

In order to round off the subject of Koffler’s musical fascinations related topically and geographically to the city of Vienna, let me mention the other work that, as he claims, made the greatest impression on him – namely, Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck, which he saw 18 years after Parsifal, most likely on 22 June 1932 during the ISCM (International Society for Contemporary Music) Festival, where Wozzeck, already present on the stage for two years, was shown as a fringe event.[4]

In the context of the Viennese production and Berg’s enthusiastic opinion about this work, let me quote the conclusion of an interesting review of the 1930 premiere written by Max Graf, an eminent Austrian critic-musicologist and great promoter of the then contemporary music, whose comments fully harmonise with Koffler’s fascination:

There came an enthusiastic applause, from the boxes and the stalls as well. One may assume that everyone was aware of the historic significance of that moment, of the kind we haven’t seen since the first Viennese performance of ‘Salome’. After the triumphant reception of ‘Wozzeck’, Vienna’s musical life can hardly stay the way it was even until yesterday.

(Der Tag, 2560 (1930), p. 8).

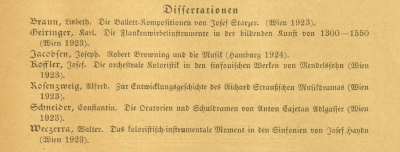

Koffler’s second stay in Vienna (1920–23/24?) is mostly associated with resuming his studies (interrupted by the war) and his doctoral defence in June 1923. His PhD dissertation on Orchestral Colours in Symphonic Works by Felix Mendelssohn was mentioned by a well-known professional German periodical (Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft, 1 (1924), p. 63) as one of the most important doctoral theses presented at the Institute of Musicology in that year.

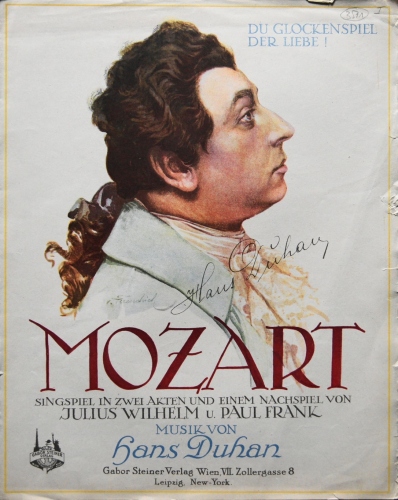

It was a theatre specialising in operettas, vaudevilles, and revues. Koffler also collaborated with other musical institutions in the city. On 2 June 1923, Vienna’s Volksoper presented the world premiere of Hans Duhan’s[5] singspiel Mozart.

A Neue Freie Presse reviewer (signing his text as ‘r’) reported in the morning issue on 3 June (21095, 13) that Hans Duhan (who had composed the music but also sang the title part and directed the production) quoted very few melodies by the great Mozart himself. Instead, the spectacle was dominated by highly successful, charming and graceful new melodies composed by Duhan specially for this purpose, of which the reviewer mentions one titled& Du Glockenspiel der Liebe. The piece was arranged by Koffler and printed with three others in the year of the world premiere by the extremely popular international publisher Gabor Steiner Verlag[6], specialising in favourite tunes written by major operetta and light music composers, such as Franz Lehár, Oscar Strauss, and many others.

How did Koffler manage to enter Vienna’s musical circles associated with that prominent editor? This is an intriguing question. His personality and expertise most likely played a role, as also did his contacts established in the early 1920s through the said collaboration with luminaries of popular music – the Bürgertheater and its head Oskar Fronz Sr. This may in turn have led to Koffler’s collaboration with Hans Duhan on the Volksoper project, and eventually with Gabor Steiner Verlag.

Koffler was notably successful in dividing his attention between studies and active participation in the city’s musical life, as evident from certain significant dates. The premiere of the singspiel Mozart on 2 June 1923 (at which Koffler may have been present) took place just three days before his written application for admission to doctoral exams, which he proceeded to take in the very same month (completing them on 6 July).

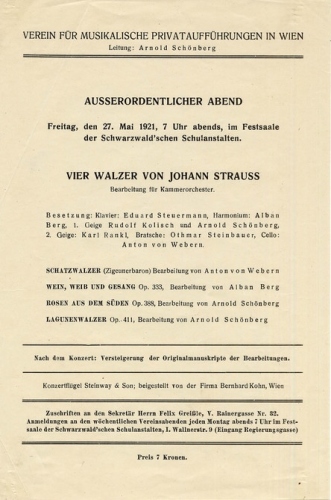

with pursuing his interest in the Second Viennese School (the music of Schönberg’s and Berg’s circle) – we do not know. According to Maciej Gołąb (Józef Koffler, Kraków, 1995, 210) he met Berg in person in 1921. Did he attend the concerts organised by the Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen (Society for Private Music Performances, est. 1918 by Schönberg)? Did he browse the press for reviews? On 27 May 1921, a well-known ‘außerordentlicher Abend’ of his idols, organised by the Society, was held in Vienna. The programme comprised four waltzes by Johann Strauss as arranged by Anton Webern, Alban Berg, and Arnold Schönberg.

or at other musical evenings held by the Society (clearly advertised as open to non-members, e.g. in Neue Freie Presse, 20874 (1922), p. 9), we have indirect evidence that he knew about these projects or at least read about them. In 1922 as well, the Neue Freie Presse and other Viennese papers regularly reported on, and enthusiastically reviewed, performances of works by the three Viennese School composers listed above.

Though Koffler moved to Lwów in 1924, Vienna continued to play some role in his life. Of all Polish contemporary composers, in the 1930s he would be the one most frequently mentioned in Vienna’s music circles.

Piotr Szalsza

English translation by Tomasz Zymer

1 In my essay titled ‘Wiedeńskie spektrum i Bruno Schulz’ [Bruno Schulz and the Viennese Spectrum], Schulz/Forum, 19–20 (2022), 229–252, https://doi.org/10.26881/sf.2022.19-20.12, I attempted a reconstruction of the wide spectrum of cultural events in Vienna that the young Koffler may have witnessed.

2 Did Józef Koffler leave Stryj in June, directly after his final exams, or, like the 20-year-old Bruno Schulz, in the autumn – reporting at the Zentralstelle der Fürsorge für Flüchtlinge aus Galizien und der Bukowina (Central Aid Agency for Refugees from Galicia and Bukovina) in order to receive a welfare benefit as a war refugee? Answers to these and many other questions related to Koffler’s both periods in Vienna can probably be found in several Viennese archives that still remain unresearched in this context.

3 Premiered on 14 January 1914, it was the first Austrian production of this work, musically directed by Franz Schalk, the Court Opera director, with sets by the great Alfred Roller. Arnold Rosé himself was the concertmaster.

4 The title part was sung by Cracow-born Josef von Manowarda. Rose Pauly sang Maria. Clemens Krauss was the music director, and the whole was directed by Lothar Wallerstein (Neue Freie Presse 24344 (1932), 15).

5 The leading Austrian baritone Hans Duhan performed at Vienna Opera for 26 years following his 1914 debut. He was the first Almaviva and Papageno at Salzburg Festival. He also sang ‘new music’. In 1927, he appeared as Daniello in 21 spectacles of Ernst Krenek’s opera Jonny spielt auf.

6 Gabor Steiner, long-time director of Viennese theatres and publisher, was the father of the major Hollywood composer Max Steiner.