Musicology

Józef Koffler graduated in musicology from the University of Vienna, where he studied, among others, with Guido Adler (who also supervised his doctoral dissertation). Adler was one of the founders of that discipline, and it was he who divided musicology into historical and systematic. Both fields were equally important for him (cf. G. Adler, ‘Umfang, Methode und Ziel der Musikwissenschaft’, Vierteljahrsschrift für Musikwissenschaft, I, 1885).

Koffler’s doctoral dissertation Über orchestrale Koloristik in den symphonischen Werken von Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy [On the Orchestral Colours in the Symphonic Works of Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy] combined both these research areas since its author discussed Mendelssohn’s style (part of historical studies) and subsequently the problem of the psychology of musical colours and their application as well as acoustic qualities (part of systematic musicology). In his later articles, Koffler frequently combined the fields of historical and systematic musicology. He often took up sociological topics, and published works on music psychology and pedagogy. He wrote almost nothing on comparative (or ethno-) musicology, which was strongly emphasised in Vienna. His interests were nevertheless very wide, and he shared his research with his readers.

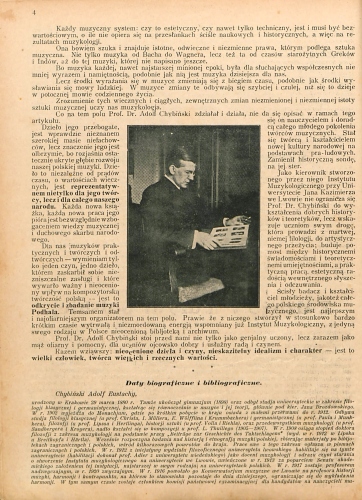

Koffler did not write any separate text that would present his views on musicology as an academic discipline. He nevertheless did refer to this subject in his 1927 biography of Adolf Chybiński, printed in Muzyk Wojskowy to mark ten years of that latter scholar’s professorship. Koffler opens the laudatory paper with praise for Chybiński’s achievements. He then proceeds to explain the term ‘musicology’, which he defines as ‘a scientific way of approaching the history of music’ (‘Prof. Dr. Adolf Chybiński’, Muzyk Wojskowy 7, 1 Apr. 1927, 4).

Such a definition differs from Adler’s approach in that it limits the discipline to historical musicology alone. All the same, Koffler also refers to systematic musicology when he writes about musical aesthetics:

Musicology teaches us what music really is, what it expresses and how it can best do it.

Scientific research consists, he claims, in a ‘re-evaluation’ of each musical system (interpreted as an aesthetic, purely technical system). Musicology

discovers centuries-old and immutable laws on which the musical art depends.

This concerns ‘not only music from Bach to Wagner, but also that of the ancient Greeks and Hindus’, that is, from outside the Western European canon (ibid.).

Koffler does not mention folk music as such, though. In their acceptance of the primacy of historical over systematic musicology, these definitions reflect Chybiński’s rather than Koffler’s own views, since the latter author was clearly more influenced by Vienna.

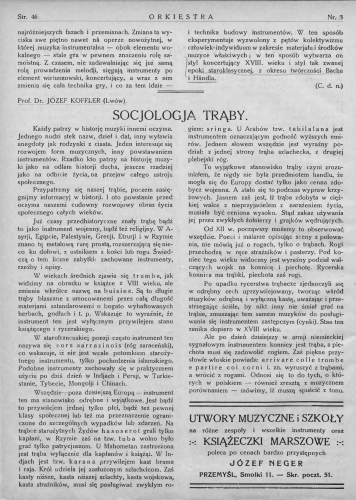

Koffler first comments on this subject in 1926, when he mentions e.g. the impact of sounds on our sensory nervous system. He claims, among others, that ‘art only becomes music after we have managed to transmit the sonic impulses we have received to our consciousness and combine them there in an appropriate manner’. He also refers to such terms as ‘hearing’ vs ‘understanding’ music (‘Musical Training’, Orkiestra, 3, December 1930, 36).

He discusses the impact of music in the context of musical forms:

Melodic elements stimulate our sensory nervous system and correspond to it; harmonic elements are related to emotions and impressions; finally rhythmic elements reflect but also stimulate the mechanics of movement and metabolism.

(‘Problems of Music Continued’, Muzyk Wojskowy, 11, 15 Dec. 1926, 5–6).

Concerning the impact of a musical work on the listener’s thoughts and emotions, he writes:

There is nothing to understand in music; music can only be felt.

(‘Problems of Music’, Muzyk Wojskowy, 5, 15 Sept. 1926, 4–5).

In this context he refers not only to the past, but also to most recent music and the enormous changes in composers’ means and ways of expression. Writing about orchestral colours (the topic of his doctoral dissertation) he admits that research into physical phenomena proves insufficient to explain our sensory perception of sound colour. For this reason, he proceeds to explain some related psychological processes.

Koffler views the history of music primarily as the story of personalities ‘that have played key or leading roles in music history’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy, 4, 15 Feb. 1927, 8). By ‘personality’ he understands ‘a development of individuality’ that liberates itself from common influences. Sociological issues are a frequent aspect of his texts on music history. According to Koffler, Bach and Handel were responsible for securing the domination of German music. Nevertheless, their outputs differ in that Bach ‘simultaneously laid the foundations for the future, whereas Handel followed the trends of his time’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy, 18, 15 Sept. 1927, 7–8). Sociologically, Handel ‘was a courtier throughout, and in principle a man of the previous era’, whereas Bach (despite the periods of service at courts) ‘was and remained a burgher, like Beethoven after him’. Bach and Beethoven also stood up for their personal rights, Koffler observes. Bach simultaneously ‘built a bridge between courtly and bourgeois art’ (ibid.)

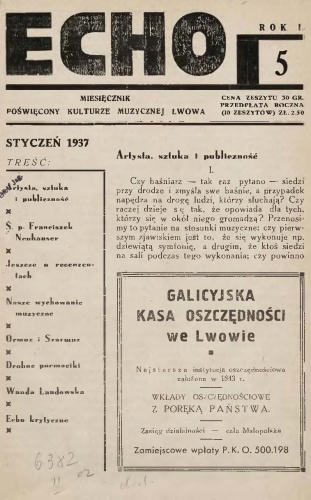

Koffler points out that the opera ought to be studied in its social context, ‘starting with the opera as an artistic phenomenon’ and incorporating such research subjects as, among others, the links between plot background and the life of the period when the given work was composed, the development of the singer’s personality in the context of the role(s) he or she performs, and the operatic audience (‘Art, Society, and the State’, Echo 2, October 1936, 1–4).

Does the performance of a work target the audience, Koffler asks, or does the artist ‘talk to himself in his work’? His answer is unequivocal: ‘Art exists for the audience, or it doesn’t exist at all.’ He invokes the authority of Leo Tolstoy for his claim that ‘art is one of the means of connecting people. Koffler defines art as ‘concentrated, condensed, abstracted sense of being alive’, and the artist as a ‘great intermediary’ (‘The Artist, Art, and Audience, Echo, 5, January 1937, 1–4). He deems the connection between artist, material, and audience necessary to art’s existence. Every musical work ought to have its proper audience: ‘every work should appeal to those to whom it is meant to appeal’ (ibid.)

He stresses that in the case of music (and other artistic disciplines, too) its value should by no means be measured by the size of the audience. Aware that opera houses are making losses, he nevertheless rejects as absurd the demand to maintain only those public institutions that ‘produce surplus’. ‘Art does not exist for the purpose of making money,’ he claims (‘Art, Society, and the State’, Echo, 2, October 1936, 1–4).

Koffler views choral singing as a reflection of thinking in terms of community. He describes the organ as a ‘collective’ instrument made up of many pipes and thus ‘the least personal’. The organ is also universal due to its wide range (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy, 6, 15 March 1927, 8–9). There has never been anything like ‘the society’s attitude to the composer’s work’, he emphasises, since ‘high artistic standards are invariably an asocial phenomenon’, and only light and dance music appeals to the wide masses (‘New Polish Music’,Tęcza weekly’s survey, Part II, Tęcza 4 (1935), 39).

Unlike many Polish musicologists between the world wars, Koffler is not concerned with ethnomusicology and refers to problems of folk music only sporadically, in the context of the role of the radio. He considers folk repertoire as ‘popular’ or ‘entertainment music’, that is, ‘one that a physically and mentally exhausted radio audience may still comprehend and [emotionally] experience.’ ‘Mapping the best paths for folk music is one of the radio’s greatest responsibilities’, he claims (‘The Radio’s Musical Problems’, Muzyka 1–2, Jan. –Feb. 1932, 23–25). He stresses the importance of promoting folk music in the society. Though he does not write about folk music, he takes it up as a composer, for instance in his Forty Polish Folksongs (1925) and Polish Suite, Op. 24 (1936).