His name triggers associations, first and foremost, with dodecaphony – the revolutionary composition technique invented by Arnold Schönberg. Koffler was the first artist to apply it in Poland and most likely in the whole of Central-Eastern Europe. Despite their innovative character, Koffler’s works admittedly did not win proper recognition in Poland, but they found appreciation abroad, as evident from their being performed at festivals held by the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM: Oxford 1931, Amsterdam 1933, London 1938) and printed by such prestigious European publishers as Universal Edition and Senart. Apart from Fantasia on Songs by Niewiadomski (printed by G. Seyfarth in Lwów), no other piece by Koffler was published in Poland.

Characteristics of Creative Output

All of Koffler’s output should undoubtedly be considered as extremely significant to twentieth-century Polish music history.

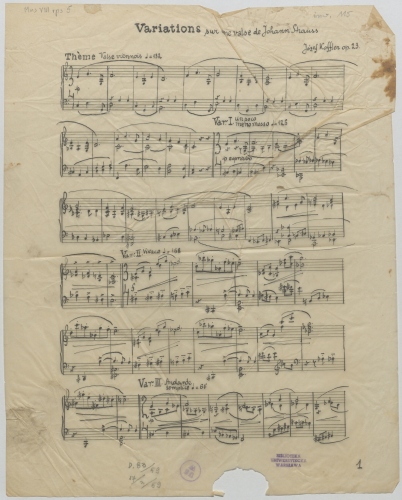

On the one hand, Lwów-based journalists, critics and musicologists favourable to Koffler (including Alfred Plohn and Jerzy Izydor Freiheiter, but also Tadeusz Majerski, Seweryn Barbag, and Stefania Łobaczewska) not only took care to report on and appreciate his output, but they also promoted it and even distinguished it in a way among the then dominant trends and tendencies. It is to Freiheiter that we owe rather precise analyses of form and technique in many of Koffler’s works. On the other hand, some texts betray unfavourable attitudes, and even more clearly – the failure to understand Koffler’s artistic aspirations and the principles of twelve-note technique. For instance, Stefan Kisielewski did a hatchet job on Koffler in his review of Variations sur une valse de Johann Strauss for piano, Op. 23 (Muzyka Polska 6 (1936)), where he accused the composer of completely lacking invention and ‘form-building ingenuity’. Similarly, Jan Adam Maklakiewicz discussed a 1936 Warsaw performance of Fifteen Variations for string orchestra in a review (Kurier Poranny, 13 Jan. 1936) whose very title announced: ‘The Horrors of Twelve Semitones’.

As a composer, he underwent a major stylistic evolution that reflected both his personal development and the impact of historical upheavals.

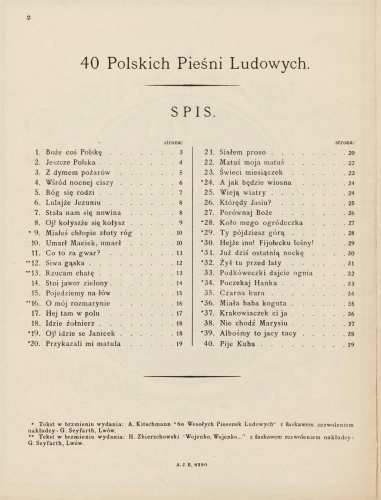

This phase cannot be studied in its entirety since little of Koffler’ music survives from 1917–1925, and he destroyed all of his orchestral works from that time. Nevertheless, his then aesthetic most likely combined influences from Eastern and Western European traditions as well as elements of Oriental music. In Zwei Lieder, Op. 1 to words by German poets, the French impressionism meets post-Wagnerian Romanticism. Most interesting is Koffler’s modernist approach to Polish folklore as reflected in Forty Polish Folksongs. These pieces, far from imitating common models, look for ways to derive consequences from the folk tunes, each of which (as he wrote in Drei Begegnungen, Wien 1934) ‘is a living organism that generates its own harmony, counterpoint, texture, voice leading, type of sound and timbre’.

The turn towards dodecaphony in 1926–1927 was an artistic breakthrough for Koffler. It took place in three piano cycles: Musique de ballet, Op. 7, Musique. Quasi una sonata, Op. 8 (dedicated to Szymanowski) and Fifteen Variations, Op. 9 (dedicated to Schönberg). By combining dodecaphony with classical forms, Koffler laid the foundations for a unique individual style, which crystallised in the next, mature phase of his work (1928–1940).

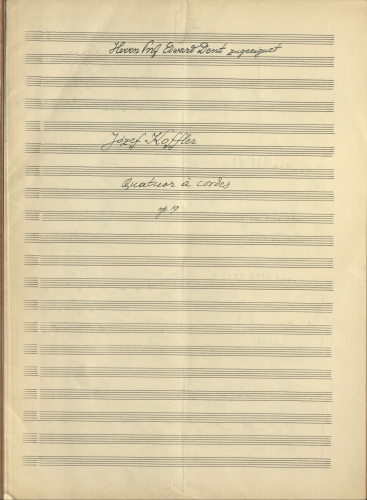

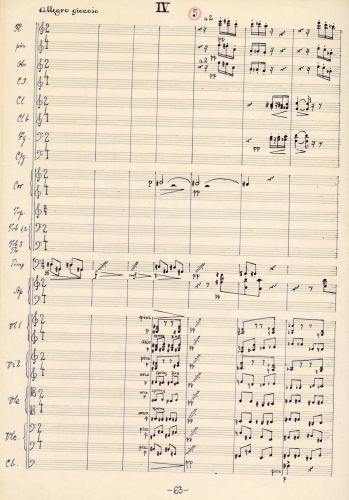

It starts with String Trio, Op. 10, which earned him success at an ISCM festival. Other music from that time includes four symphonies (Opp. 11, 17, 21, and 26), works for voices and instruments (the cantata Die Liebe, Op. 14, Four French Songs, Op. 22, and the Zeitoper-type oratorio-ballet Ales durch M. O. W., Op. 15), as well as Sonatina, Op. 12, Piano Concerto, Op. 13, and Variations sur une valse de Johann Strauss, Op. 23. In those last three pieces, Koffler improved his twelve-note technique and involved it in an intriguing dialogue with musical history, drawing on works by Clementi, Schumann, Field, Chopin, and the Viennese waltz master. At the same time, he built the form and sound qualities in his works in ways which rendered them more accessible to the audience than what is stereotypically thought of dodecaphony.

Written in 1934, it turns out to contain music material that became the prototype for Symphony No. 4, first performed in 1940 in Lwów, already under the Soviet occupation. The Symphony offers proof that, in the new social and political circumstances, the composer still strove to retain his artistic identity.

In 1936–1939, Koffler’s artistic explorations became less intense, and he composed much less, focusing mainly on arrangements of works by other composers (Little Suite after J.S. Bach and orchestrating the Goldberg Variations) or from tradition (Polish folksongs and dances in Polish Suite for small orchestra, Op. 24.

Apart from Symphony No. 4, he added to his catalogue the Joyful Overture, Op. 25 (for the anniversary of the Red Army’s capture of Lwów), piano pieces for children, and Ukrainian Sketches for string quartet, Op. 27. Despite its ideological context, the Overture may have retained traces of his earlier aesthetic. In the last work, based on well-known Ukrainian tunes, the composer returned to folkloric inspirations. This time, however, he incorporated folk motifs in ways that do not quite exploit their structural wealth and artistic potential. This stylistic change, enforced by the political context, was a step back in comparison with his earlier achievements. The ‘Soviet period’ also yielded more arrangements of other composers’ works: the favourably reviewed Händeliana (thirty variations on Händel’s passacaglia) as well as a reconstruction and completion of Ludwig Minkus’ ballet Don Quixote.

We have no proof or even indirect evidence that Koffler composed any music in his last months spent ‘on the Aryan Side’, when he undoubtedly focused on survival and on rescuing his family. Even if we assume that creative work was his standard daily ritual or (conversely) a way of cutting himself off from the threatening reality of Distrikt Galizien – the possible effects of such labours have irretrievably been lost with his and his family’s death.

was closely linked to the European avantgarde of the early twentieth century and to his own original transformations of concepts introduced by the Second Viennese School. At the same time, it included some distinctly national elements. His abruptly interrupted and thus incomplete oeuvre is nevertheless unique in European music, particularly with respect to the fascinating ways in which Koffler strove to attain balance between respect for tradition and desire for innovation, between the avant-garde’s universal language and national elements, between experimentation and comprehensibility of artistic message. Koffler himself most aptly defined his artistic stance when he described himself as belonging to ‘Berg’s group […] which aims to contain in dodecaphony all the old and new means of expression, without rejecting the abstract ones or ignoring the “music-makers’” craft’ (‘Twelve Tones’, Wiadomości Literackie 10 (1936), 6). He was fully successful in implementing these briefly stated principles.