History of Music and Composers (after 1900)

Koffler aptly compares the ca-1900 breakthrough in music to the one that took place in the Florentine circles three hundred years before (with the emergence of dramma per musica), ‘though one may not grant impressionism an importance comparable to that of the Renaissance, from either the absolute or developmental perspective’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 2, 15 Jan. 1928, 7–8). Himself, however, Koffler is never enthusiastic about impressionism. He sees it mostly as an ‘anti-Wagnerian reaction’, and claims that the ‘avoidance of continuity’ characteristic of this trend reveals ‘all the pros but also all the cons of that style’ (ibid.). In the process of mapping out new directions in music before 1918, he attributes a much greater role to Igor Stravinsky than to Debussy.

It was Stravinsky, Koffler claims in 1932, who quickly eclipsed Debussy’s earlier impressionist aesthetic. He emphasises that Stravinsky ‘played with forms’ by advocating brevity in works’ structure, and ‘created those forms with full awareness of his goals’. He also praises Stravinsky for ‘extraordinary comic talent’ (‘Igor Stravinsky’, Muzyk Wojskowy 11, 1 June 1927, 2) and stresses that rhythm played the greatest role in Stravinsky’s output. Much more highly than he praises Debussy, Koffler extolls Max Reger as the ‘master of the musical line’ and ‘contrapuntal genius’ superior to Bruckner and everyone else except Bach.

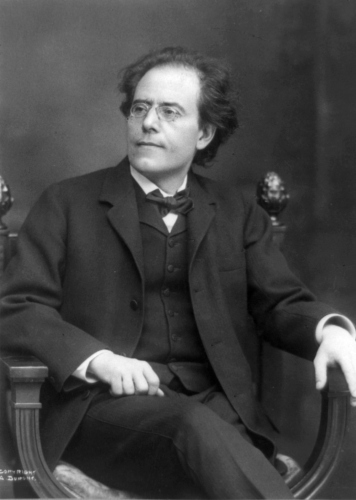

Koffler recognises Mahler as the artist who ‘made a great breakthrough’ since he attained a new symphonic ideal, surpassing Brahms and Bruckner in this genre (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 9, 1 May 1928, 4–6). Seventeen years after Mahler’s death, Koffler writes of him with great reverence: ‘Beyond a great artist, we find an even greater human being’ (ibid.). This was by no means a common view in the 1920s, when Mahler was no longer as highly respected as before.

Koffler considers Mahler as the first modern composer, who managed to synthesise ‘all the forces contained in German music’. He stresses that Mahler liberated himself ‘with admirable consistency’ from the influence of Wagner’s operas (ibid.). He also freed the symphony from academic strictures and restored the genre to ‘vibrant life’. Koffler thus compares Mahler to Beethoven and his Ninth, arguing that both these composers created their own individual means of expression. Mahler ‘used choirs to attain Berlioz’s ideal in his Symphony No. 8 (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 1, 1 Jan. 1928, 8–9). With regard to harmony, Koffler describes Mahler’s technique as ‘the last expression of tonality’ which ‘contains all the germs of future developments’.

According to Koffler, Mahler addresses his music to the listener’s soul rather than the mind, which ought to be interpreted as a rejection of intellectualism in music.

He maintained that, in opposition to technical artistry, spiritual propaganda, and 'the Romantic vanity of the individual,' Mahler's music strove to reveal the soul 'on the broadest possible foundation.' Writing in 1928, Koffler acknowledged that it was still too early to assess the extent to which Mahler had succeeded in realizing this goal.

Richard Strauss was, according to Koffler, ‘the last link in the natural line of development’ delineated in music history by Bach. Strauss was ‘a polar extreme in relation to Bach’s symbolically primitive art’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 9, 1 May 1928, 4–6). Koffler stressed Strauss’s major contribution to the process of doing away with the major-minor tonality. Strauss ‘drew the ultimate conclusions from the Romantic way of thinking’, ‘leading the voices uncompromisingly’ in some cases ‘without paying attention to chords’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 4, 15 Feb. 1928, 5–6). Koffler notes that Strauss introduced extramusical sounds (such as noises) in his works. In 1928, Koffler saw Hans Pfitzner and Frederick Delius as continuators of Richard Strauss’s musical direction.

Koffler labels Schönberg and Karol Szymanowski (sic!) as representatives of expressionism (a term he first used in 1928), defining their outputs as ‘self-sufficient music’ that ‘steers away from philosophising music’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 9, 1 May 1928, 4–6). Koffler adds that the expressionists wrote symphonic poems in their early period (among which he lists Schönberg’s Pelleas und Melisande, Op. 5 and Szymanowski’s Penthesilea, Op. 18, as well as Franz Schreker’s Ekkehard, Op. 12 and Max Reger’s Vier Tondichtungen nach A. Böcklin, Op. 128).

Though Koffler never met Schönberg in person, he considered contact with that artist (via his handbook of harmony, works, and correspondence) as crucial to his music education. As early as 1928, Koffler hailed Schönberg in the Polish press as the most important figure in the history of musical developments over the preceding three decades. In 1934, he wrote an article marking Schönberg’s sixtieth birthday (previously, he had also given a lecture on this composer on Polish Radio). Fully aware that the Viennese artist’s output was not viewed favourably by everyone, Koffler begins with this statement:

It is my firm and unshaken conviction that Arnold Schönberg is one of the greatest persons and artists.

(‘Arnold Schönberg’, Orkiestra 12 (1934), 187–188).

Schönberg’s greatness lies, he claims, in the skilful use of composition technique, which allows him to solve the problems set for himself in each work so completely ‘that they cease to exist at all’. Koffler calls Schönberg ‘the most uncompromising’ and ‘most extreme’ composer, ‘the only revolutionary in our art’. Among Schönberg’s greatest achievements, Koffler lists the emancipation of dissonance and creating a scale of twelve equal notes as a new form-building principle. In this context, he invokes his personal links to Schönberg (albeit without openly stating whether they met in person or not): ‘his [Schönberg’s] character must surely charm and fascinate all those who have had the opportunity to come in contact with him, in person or via his writings’ (ibid., 188).

Koffler compares the achievements of Schönberg and Stravinsky with regard to their respective ways of leaving the major-minor tonality behind. The ‘more reflective’ Schönberg inductively devised a new system ‘which he believes to be, and which actually is, the only possible way of keeping a tight aesthetic and technical rein on atonality, a construct which he then brilliantly implements’ (‘Igor Stravinsky’, Muzyk Wojskowy 11, 1 June 1927, 3). Koffler views Stravinsky as a more impulsive artist who

uses his genius to create works, but leaves the deduction of a system to others. Schönberg is thus the deeper one, and Stravinsky – the higher.

(ibid.)

While Schönberg’s concepts (or ‘school’) aim at ‘the most radical transformation of all the means of expression’, Koffler claims that Webern’s ‘school’ ‘sublimates the abstractness of some expressive means’, whereas Berg’s ‘school’ (of which he considers himself a part) ‘aims to incorporate both old and new means of expression within the twelve-note method’ (‘Twelve Notes’, Wiadomości Literackie 10, 8 March 1936, 6).

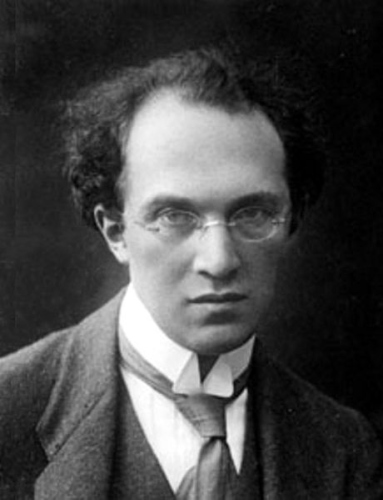

In Berg’s case, Koffler not only knew his output well, but was also a close acquaintance, as suggested by the phrasing of the obituary published by Koffler after Berg’s death in 1936. In that tribute, Koffler calls Berg ‘one of the greatest music composers’ and adds: ‘I have lost a great, noble, and supportive friend’ (‘Alban Berg’, Orkiestra 1, January 1936, 15). Koffler admits that Berg’s Wozzeck (which he heard at age thirty-six) and Wagner’s Parsifal (heard at age eighteen) made the greatest impression on him of all musical works (also in emotional terms) – which, he adds, is rare in his case, since as a professional musician ‘he listens and hears [music] analytically’, without strong emotions.

This claim notwithstanding, problems of new music frequently did provoke powerful emotions in Koffler. One example is his heated polemic with Stefania Łobaczewska concerning the achievements of the Second Viennese School. Their debate appeared in the Przemyśl-based Orkiestra and in Warsaw’s Muzyka in 1936. Koffler criticises Łobaczewska for calling Alban Berg ‘an uncompromising proponent of the most leftist trend in contemporary music’ (S. Łobaczewska, ‘At the Grave of Alban Berg’, Muzyka 10–12 (1935), 236). Sharply opposing Łobaczewska (though without directly mentioning her), Koffler defends the autonomy of music as free from political associations, and comments that ‘such discrediting but imprecise opinions had better be avoided’ (‘A Necessary Correction’, Orkiestra 2 (1936), 19–20). He also accuses Łobaczewska of not knowing Schönberg’s music well and in good-quality interpretations. Direct contact with the musical work as manifested in its performance (not merely a score study) was of great importance to Koffler.

The Austrian composer’s fiftieth birthday provided Koffler with an opportunity to present a brief profile of the artist and his achievements: ‘Schrecker [the earlier spelling – translator’s note] was the first composer after Wagner successfully to find his way in the opera, without falling into the trap of aestheticizing writing or lowbrow drama spiced with sensation’ (‘Fr. Schrecker (1878–1928)’, Muzyk Wojskowy 8, 15 Apr. 1928, 8). On another occasion, Koffler discusses Schreker’s suite (pantomime) Der Geburstag der Infantinfor a new Muzyk Wojskowy column, which aimed ‘to familiarise the conductors with noteworthy, recent and most recent works, with a view to their possible performance’. The suite (premiered in 1908 in Vienna for the foundation of Kunstschau, a circle of artists centred on Gustav Klimt) was already twenty years old by that time – by no means a very recent work. Koffler notes its weak points, which he relates to the overall aesthetic of the Viennese scene at that age since ‘the sugary character of these melodies and the nearly grotesque quality of some passages’ derives ‘from the soft feminine asceticism of the then Vienna’ (‘The Night of Liberation (Verklärte Nacht)’, Muzyk Wojskowy 9, 1 May 1928, 10–11).

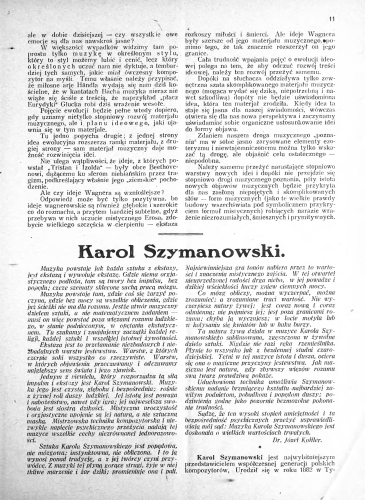

In 1928, Koffler described Szymanowski’s output as a ‘synthetic union of opposites’, combining ‘intensive Romantic content’ with ‘extensive expressionist means’ (‘Karol Szymanowski (The Composer’s Symphonic Concert)’, Muzyk Wojskowy 5, 1 March 1928, 4–5). To Koffler, who valued the creative impulse in music (apart from mathematical speculation), Szymanowski was one of the few ‘to possess that power of impulse and ecstasy’. ‘His music is pure, deep, and straightforward,’ Koffler claims, ‘impulsive rather than cerebral, instinctive rather than calculated’ (‘Karol Szymanowski’, Muzyk Wojskowy 1, 1 Jan. 1928, 11). He also highly values Szymanowski’s technique (‘the hand of the craftsman does not offend in any respect’). It is through ‘technique informed by the spirit’ that Szymanowski was able to give ‘shape in sound to the most complex impulses, inspirations, and drives of the soul’. Koffler views Szymanowski’s music as ‘excellent and with great lasting value’. In the same year (1928), Koffler published his Musique. Quasi una Sonata for piano, Op. 8, dedicated to Szymanowski as a token of appreciation for that artist.

Symphony No. 3 ‘Song of the Night’, Op. 27 (which he heard during its world premiere in Lwów under Adam Sołtys, 1928) delighted Koffler with its condensed form, which he describes as ‘a brilliant synthesis of spiritual depression and salvation’. The choral part, he observes, does not merely reflect textual meanings but becomes ‘an instrumental group within the vast instrumental family’. Koffler also highly praises The Love Songs of Hafiz, Op. 26, which ‘open up unknown worlds’ of harmony, rhythm, and instrumentation.

There are many well-known Polish twentieth-century composers, such as Mieczysław Karłowicz and Ludomir Różycki, to whom Koffler does not refer at all. His 1927 text dedicated to Mieczysław Sołtys, head of Lwów’s PTM Conservatory (where Koffler himself was employed), calls the latter grandiloquently ‘one of Poland’s greatest composers’, quotes examples of self-correction (the composer’s remake of his opera Panie Kochanku, premiered in 1924 in Lwów), and calls that work ‘the best Polish comic opera, whose finale is a masterpiece of operatic writing at large’ (‘Mieczysław Sołtys’, Muzyk Wojskowy 2, 15 Jan. 1927, 7).

Koffler’s published texts concerning his own music contain many original opinions, unlike his comments on other composers, which primarily had a popularising function. There are several (rather brief) press notes in which he discusses his works and technique.

One of the compositions he introduces is Sielanka [Idyll], Op. 4 (1925)

This composition was presented two months before (in April 1928) during a PTM concert under the baton of Adam Sołtys in Lwów. Koffler does not provide any detailed description of the musical scenes since, as he explains, ‘I am not fond of programmes in music’ (‘Several Notes on My “Idyll”’, Muzyk Wojskowy 11, 1 June 1928, 12). Looking at his work in retrospect (more than four years after its completion), he distances himself from it (‘this piece is very foreign to me now’). In this context, he comments on music composition in general, claiming that ‘our task is to have ideas and predict what they need to come to life’. Acquiring knowledge of music theory is, in his view, by no means sufficient for new concepts to emerge.

Today I know that form is not what we learn from handbooks and classroom analyses. Form is a construction with varying degrees and centres of gravity, with a climax, or else a free matrix made up of numerous equal polyphonic and mass progressions, or a vessel as diverse as the world and its creatures.

For this reason, he argues, ‘one should not complain when our own children take their own path’ (ibid.).

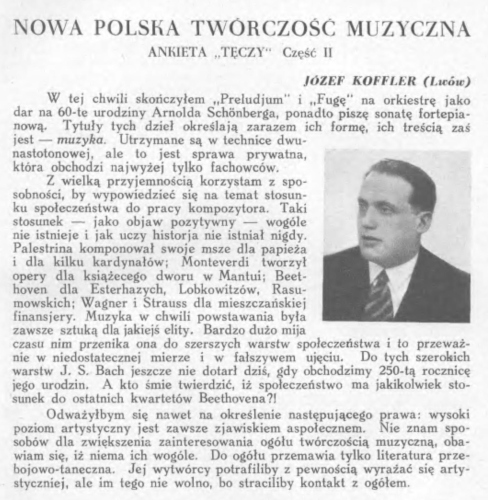

In his brief elucidation of twelve-note technique in contemporary music, Koffler calls it ‘just a new phase in the historical process of organising sound material’ (‘Twelve Notes’, Wiadomości Literackie 10, 8 March 1936, 6). Scales other than major and minor, such as the pentatonic scale, have already been used in the history of music, Koffler says. He emphasises that the difference in relation to the major-minor tonality lies in the approach to harmony, which in twelve-note music ‘is a chance result of the juxtaposition of voices’ regulated by the composer, and therefore ‘belongs more to the realm of style’, which depends not on technique in this case but on artistic individuality ‘and its approach to the expressive tools’ (which is a reference to Adler’s theory of style). Dodecaphony itself is, according to Koffler, primarily a form-building principle which yields ‘a new organic wealth of harmony and counterpoint, of sound and timbre’. In 1935, Koffler wrote in Tęcza weekly that he had never viewed technique as an end in itself and that the true content of his works is music, though ‘they are written in the twelve-note technique’ (‘New Polish Music’, a survey, Part II, Tęcza 4 (1935), 39). In Wiadomości Literackie, Koffler defines himself as a representative of the ‘school’ of Alban Berg (rather than that of Schönberg), and describes his 15 Variations d’après une suite de douze tons for piano, Op. 9 (1927) as a ‘coursebook’ introduction to twelve-note technique rather than a fully-fledged ‘work of art’ (‘Twelve Notes’, Wiadomości Literackie 10, 8 March 1936, 6).

The sharp polemic on Koffler’s music that took place in the Polish press in 1936 (discussed in detail by Maciej Gołąb in his monograph) was occasioned by a performance of that composer’s Variations, Op. 9a. Konstanty Regamey criticises this cycle as ‘unremarkable’ despite ‘Koffler giving proof of his great musical knowledge’ (K. Regamey, ‘The Philharmonic: Askenaze, Horenstein, and Koffler’, Prosto z mostu 3 (1936), 7). Felicjan Szopski describes the Variations as ‘brainwork’, but the effect – as ‘monotonously tiresome’ (F. Szopski, ‘A Philharmonic Concert’, Kurjer Warszawski, 12 Jan. 1936, 17). Koffler responds to this criticism in Wiadomości Literackie, explaining his artistic intentions and the role of dodecaphony in his music.

Koffler’s Variations sur une valse de Johann Strauss for piano, Op. 23, stirred up even stronger emotions.

In a review that followed the work’s publication, Stefan Kisielewski does a hatchet job: ‘No one dares to be the first to call the king naked though everyone whispers about it in secret’ (S. Kisielewski, ‘Józef Koffler: Variations sur une valse de Johann Strauss op. 23. Piano solo. UE, Wiedeń, Str 16’, Muzyka Polska 6 (1936), 401–404). The charge was that Koffler cared exclusively for the twelve-note technique (i.e. for construction) at the expense of artistic value, which suggests that he only targeted an audience with a suitable theoretical background. Koffler responded in the following year by saying: ‘I have been warding off attempts automatically to associate my name with dodecaphony’ (‘The Duodenum in “Muzyka Polska”’, Echo 6 (1937), 7–9). He was hoping that his works would be listened to and assessed just like any other music, without any special preparation and without prejudice. Not all of his compositions, he reminds his readers, were written in the twelve-note technique. Unlike his adversary, Koffler claims, he likes polemics ‘on the level of a thoughtful mind’. Kisielewski did not take up the gauntlet, though. ‘The unseemly tone of Koffler’s article exempts me from the duty to polemise with it,’ he writes, and concludes: ‘I do not know Mr Koffler and have never even seen him (which I certainly do not regret now)’ (S. Kisielewski, ‘Reply to Mr Koffler’, Muzyka Polska 3 (1937), 144).