Contemporary Musical Culture

Current music life in interwar Poland, discussed mostly from the perspective of the city of Lwów, was a major topic for Koffler the journalist. Musical activity in Poland, he concludes in 1934, has never been an expression of social culture at large. Instead, it was a local phenomenon centred on just a few cities that boasted musical traditions (Lwów being one of them). In order for musical life to be revived, the economic situation must improve, too. Regrettably, in the wake of the recent war both the young and the older generations have become musically indifferent, ‘devoid of any significant attitude to music as an art’ (‘The Artist, Art, and Audience, Echo 5, January 1937, 1–4). Koffler dedicates much space to transformations of musical culture brought about by the radio.

A sense of quality, he claims, is the foundation of true musical culture.

The distinction between classical and light music should not follow aesthetic and artistic criteria since popular music can prove to be of very high quality whereas ‘serious’ works may often turn out to be ‘devoid of any significant artistic value’ (‘The Radio’s Musical Problems’, Muzyka 1–2, Jan. –Feb. 1932, 23–25). As early as in 1928, Koffler argued for an annual chamber music festival in Zakopane (modelled on that held in Baden-Baden).

Sixteen years after Poland regained independence (in 1918) Koffler describes the mental paradigm that rules supreme in the country as ‘an engineer’s perspective’ which ‘has social needs at heart but no imagination and no wide horizons’ (‘Polish Music under Threat’, Muzyka 10/12, Oct.–Dec. 1934, 370). His appeal is to save whatever can still be rescued, including the existing opera houses, orchestras, and music schools. He also deems it necessary to build foundations for musical culture in the future generations by reorganising general musical education in primary and secondary schools, reforming musical education for the common benefit, creating organisations of music composers and performers, as well as ‘converting the radio into an educational institution’ (ibid.).

On some occasions, Koffler sharply criticises the standards of contemporary music life.

He writes about the situation in Lwów in 1936: ‘Lwów’s concert life has been perverted to its limits and it represents a total decline’ (‘The Change of Concert Organisation’, Echo 4, December 1936, 1–3). He adds that in this respect Lwów makes the impression of ‘a backward place, the back of beyond’. He points out the small number of concerts, the costly special events meant to attract the audience (he calls them ‘sensations’), and the high fees for all concert ads and announcements, which constituted minimum 30 per cent of the total cost of organisation. His plan is to revive a music-loving audience in Lwów that would attend ambitiously programmed concerts at least twice a month.

Both as an editor and reporter, Koffler dedicates some space to concert programmes.

In his own Echo and as a music reviewer for Lwowski Ilustrowany Express Wieczorny illustrated daily (1932–1937), he often criticises poorly constructed concert programmes, also in the case of appearances by well-known artists.

Concert programming, he claims, depends on several factors: the musician’s individual talent and preference, the demands of time and fashion, as well as audience needs. He rejects the recent habit of performing a number of contemporary pieces at the end as ‘modern works call for a fresh mind’ and so they ought to be presented in the beginning. A properly functioning concert life depends on such elements as excellent performers (‘possessing imagination and a sense of artistic responsibility’), appropriate concert programmes (‘varied and not too long’), and an audience ‘that will regain its confidence in artists’ diligence and faith in the necessity of [music’s] existence and logical development’ (‘On the Reform of Concert Life’, Echo 6, February 1937, 4–5). What Koffler deems necessary in order to achieve this goal is close collaboration between the composer, performers, and the audience. He also points out that musicians need to be properly educated. Far from being ‘a mere performer’, a singer or instrumentalist ought to possess expert knowledge and use it to create apt interpretations ‘totally expressing the musical and ideological content of the work’. He also praises improvisation as the skill of the virtuosi from the past, who thanks to that practice managed ‘to find contact with their era’.

As a reviewer for Lwowski Ilustrowany Express Wieczorny, Koffler discusses, apart from concert programmes, also interpretations by various Polish and foreign musicians, including Bronisław Huberman, Artur Rubinstein, Artur Hermelin, Jerzy Hofmann, Zbigniew Drzewiecki, Ewa Bandrowska, and others.

Koffler’s ‘A Critic’s Decalogue’, printed in Muzyk Wojskowy (1928) includes such maxims as: ‘The audience is free to follow tradition and personal taste, while artists are slaves to their individualities. What is justified in the audience and the artist, is not allowed in you [the critic].’ ‘You are neither the audience’s eye or ear, but you are its conscience.’ ‘Do not base your artistic judgments on subjective expectations, however strongly and genuinely you may feel about them.’ ‘Do not see or present your personal views as inviolable acts of your personality; examine and justify them instead.’ ‘Feel capable of accepting also those artistic phenomena that do not suit you personally or even contradict your views. Your task is to assess, not to seek beauty.’ ‘Criticism is subject to the following general psychological principle: It is not strong words that achieve the effect, but the internal strength of their justification.’ ‘Success is no proof of value.’ (‘A Critic’s Decalogue’, Muzyk Wojskowy 23, 1 Dec. 1928, 8–9).

In an editorial for his own journal Echo, Koffler quotes Arnold Schönberg’s view on the qualifications necessary in a professional music critic (‘one must find a point of view that gives us insights into the essence of the given work’). Like Reiss before him, Koffler wonders whether non-expert opinions on art must be presented in the daily press; it would be much better, he argues, if it limited itself to information alone in such cases.

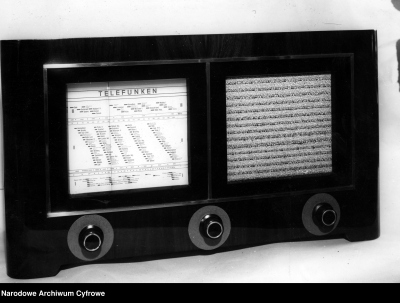

Like many other Polish musicologists (Jachimecki, Chybiński, Reiss, Barbag, and others), Koffler collaborated with Polish Radio, presenting lectures on Radio Lwów. In 1932, just a few years after the establishment of Polish Radio (broadcasting from Warsaw as of 1925 and from Lwów as of 1930), Koffler discussed technical, psychological, educational-programmatic, artistic-aesthetic, and social-economic issues related to the radio’s emergence. Psychological problems related to the radio, he notes, ‘have not been researched so far’. The radio ‘eliminates the positive impulse that music performers receive from a live audience’. On the other hand, it is thanks to the radio that great social masses can listen to music for the first time (330 thousand radio-licence holders in 1932) and ‘will be inspired to creative activity by the radio’ (‘The Radio’s Musical Problems’, Muzyka 1–2, Jan. –Feb. 1932, 23–25). The choice of repertoire gives the radio an educational role.

In another text, Koffler observes that artistic music was created for centuries with only a narrow elite audience in mind (Beethoven wrote mainly for aristocratic families, Wagner and Strauss – for the rich bourgeois financial circles). It is only with the emergence of the radio that material obstacles are now removed but ‘there remains another obstacle, of spiritual nature, to be dealt with’ (‘Radio and Musical Culture’, Muzyka 10/12, Oct.–Dec. 1935, 225–228).

An unsigned article, printed in Echo in 1937 (more than a decade into Polish Radio’s broadcasting history) and probably written by Koffler as that journal’s editor, begins with the statement that ‘the place of artistic music in radio research is still problematic to some extent’. On the other hand, the author notes that music ‘takes up the greatest part of the broadcasting time’ and that, of all the media, the radio has demonstrated the greatest possibilities of ‘influencing the widest spectrum of social strata’ (‘The Radio as a Music Educator’, Echo 7, March 1937, 1–4). The author joins the debate concerning the social role of the radio, discussing its entertainment-related, educational, and artistic functions.

Concerning the radio’s musical repertoire, Koffler notes that the principle of ‘music for everyone’ has been misinterpreted since, rather than ‘elevating the society to the level of the music’, music on the radio has stooped to the level of the society (‘Radio and Musical Culture’, Muzyka 10/12, Oct.–Dec. 1935, 225–228).