History of Music and Composers (before 1900)

Koffler dedicates relatively little space to the period before 1800.

In his ‘Compendium of Music History’ (Muzyk Wojskowy) he presents a survey of music history since ancient Greece. This includes, apart from general, also Polish music history, discussed in such sections as ‘The Polish Contemporaries of the Franko-Flemish Composers’ (Nicolaus de Radom) and ‘The Influence of the Roman School in Polish Music’ (Tomasz Szadek, Mikołaj Gomółka). Koffler describes Gomółka’s Melodies for Polish Psalter (1580) as ‘one of the most valuable and noteworthy sixteenth-century works, whose technique often goes beyond the contemporary style, particularly in its chromaticisms’ (‘Compendium of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 3, 1 Feb. 1929, 8). Unfortunately, the previously announced cycle of articles was discontinued after reaching the mid-eighteenth century (the opera buffa and the French opera).

In his brief survey of European music history from the Middle Ages to the late eighteenth century, Koffler strongly emphasises the sociological aspect and does not focus on events alone. He frequently refers to the theory of evolution in his discussion of music history. He traces various influences and inspirations from one age to another and applies Adler’s theory of style. He claims, for instance, that the idea of troubadours (as independent singers) was taken up by opera soloists several hundred years later. Writing about the beginnings of the opera (at the Florentine court at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries), he observes that, despite the initial intention to revive ancient drama, over the later decades the influence of soloist practice

soon distorted that serious style by abandoning dramatic truth and declamation

(‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 14, 15 July 1927, 6–8).

Koffler claims that

the breakthrough brought about by the courtly age and its stylistic expression depended, first and foremost, on the freedom and dominance of melody in the top part

(‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 9, 1 May 1927, 3).

In his presentation of operatic history in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Koffler emphasises its social dimension.

Johann Sebastian Bach and other greatest composers cannot be assigned to one period alone, he argued, since (in accordance with Adler’s concept of style), great masters ‘may not be reduced to a formula, and their style does not correspond to any clichés’. Their greatness, Koffler claims, did not depend on ‘inventing new things, but on perfecting what the previous and contemporary age had accumulated’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 17, 1 Sept. 1927, 6–7). According to Koffler, the reason why we know rather few compositions by either Bach or Händel is that too few of them are still presented. He compares Bach’s cantatas to ancient dramas in which ‘choral singing created, in a way, a connection between the stage and the audience’. Händel’s oratorios are, on the other hand, ‘sacred operas’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 18, 15 Sept. 1927, 7–8).

In Koffler’s view, Bach and Händel consolidated the domination of German music.

In sociological terms, Händel ‘was a courtier throughout, and in principle a man of the previous era’, whereas Bach (despite his periods of service at courts) ‘was and remained a burgher’ (ibid.).

Writing about the Viennese classics, Koffler observes that Joseph Haydn composed his symphonies for the prince’s court orchestra, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – ‘for selected invited audience’. The author stresses the importance of the French Revolution, which marked ‘the end of aristocratism as the social [basis] of music (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 19, 1 Oct. 1927, 3–4). As a result, in the second half of the eighteenth century, music began to be performed in public halls as well, and the orchestras began to grow in proportion to the growing audience.

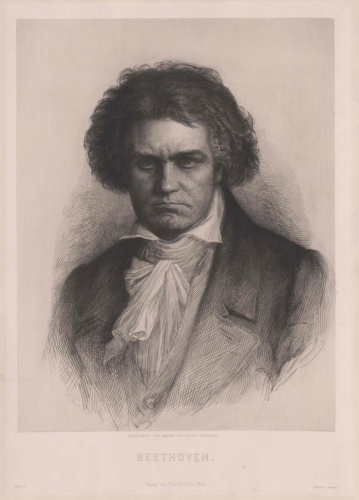

Like other Viennese musicology graduates (including Reiss, who wrote a book about this composer), Koffler frequently referred to Beethoven’s output and achievements. He placed Beethoven on the boundary between two periods, describing that artist’s contributions as ‘a perfection of Classicism’ and ‘initiating Romanticism in music’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 20, 15 Oct. 1927, 4–6).

Like Reiss, Koffler compared Beethoven to Bach.

He claimed that with his ‘fate motif’ the former ‘contributed to the series of leitmotifs initiated by J.S. Bach’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 1, 1 Jan. 1928, 8–9). In sociological terms, both composers were members of the bourgeoisie who stood up for their personal rights. Koffler argued that Beethoven did not create his greatest works for the court circles but for the ‘nameless masses’, which constitute ‘the metaphysical pillar’ of his nine symphonies and Fidelio. He pointed out that in Beethoven’s symphonic cycles the courtly dances (the gavotte and the minuet) ‘no longer function as resting points’ and their ‘formal courtly’ character is disposed of (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 19, 1 Oct. 1927, 3–4). Koffler openly described the replacement of the minuet with the scherzo as ‘the spirit of the new age and of equality’. Concerning Beethoven’s final quartets, which most of that artist’s contemporaries found inaccessible, Koffler wrote that they were only comprehended ‘by a small group of those chosen not by virtue of birth but of their minds and humanity’ (ibid.).

He pointed out that in Beethoven’s symphonic cycles the courtly dances (the gavotte and the minuet) ‘no longer function as resting points’ and their ‘formal courtly’ character is disposed of (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 19, 1 Oct. 1927, 3–4). Koffler openly described the replacement of the minuet with the scherzo as ‘the spirit of the new age and of equality’. Concerning Beethoven’s final quartets, which most of that artist’s contemporaries found inaccessible, Koffler wrote that they were only comprehended ‘by a small group of those chosen not by virtue of birth but of their minds and humanity’ (ibid.).

Koffler considers Schubert and Carl Maria von Weber as Beethoven’s ‘unwitting’ continuators. He compares their achievements:

What Schubert did for [art] song, Beethoven did for purely instrumental music.

(‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 20, 15 Oct. 1927, 4–6).

Concerning the relation between melody and text in Schubert’s works, Koffler rather uniquely invokes an analogy to the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century dramma per musica:

Schubert revived the art of incorporating a recitative and an aria within the same song insofar as the lyrics demand it, a practice similar to that initiated by the Florentine opera.

(ibid.)

He notes that Schubert’s sacred music is poorly known and underrated in Poland. Koffler calls the A Major and E-Flat Major Masses ‘masterpieces’. Schubert, he adds, also contributed to the flourishing of the waltz, later taken up by Johann Strauss.

Though Koffler’s doctoral dissertation, titled Über orchestrale Koloristik in den symphonischen Werken von Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, was not published, excerpts from that study were quoted in Polish music press (Muzyk Wojskowy, 1928; Orkiestra, 1934). In both articles based on his doctorate, Koffler distinctly draws on Guido Adler’s methodology. In the article published in Muzyk Wojskowy, he extensively quotes from Adler’s Der Stil in der Musik (Leipzig, 1911).

According to Koffler, Mendelssohn's achievement lay in introducing new stylistic elements „crucial to the development of Romanticism” – abilities of this kind he also attributed to Brahms and Reger (‘F. Mendelssohn’s Orchestral Works’, Muzyk Wojskowy 7, 1 Apr. 1928, 1–3). He then discusses Mendelssohn’s response to the claim that his works carried extramusical meanings, citing the composer’s letters in this context as well as Hermann Kretzschmar, a professor of musicology at Berlin University, who viewed some of Mendelssohn’s compositions as programme music. Koffler also refers to the opinion expressed in 1913 by the early Viennese musicology graduate Hugo Botstiber, who claimed that even Mendelssohn’s overtures for the Paulus and Elias oratorios were programmatic.

In turn, writing about Mendelssohn in the "Orkiestra" in 1934, Koffler reiterated his conviction that:

he has great skill and ease in adjusting to various styles […] he managed to introduce new stylistic points that were important to the development of Romanticism.

(‘Felix Mendelssohn’s Orchestral Works’, Orkiestra 4 (1934), 50–51).

Though Mendelssohn was a Romantic composer, Koffler claims, he ‘depended on older classical practice’ and therefore did not dismantle the existing musical forms and genres. As a composer, he argues, Mendelssohn was ‘much of a craftsman, a master in the old sense of the word’. Koffler concludes that, though craft and deliberate work might seem less noble than inspiration, ‘both are equal in status, and true art depends on both’. Where ‘these two are coordinated […] everything becomes action, work, and form’ (‘F. Mendelssohn’s Orchestral Works’, Muzyk Wojskowy 7, 1 Apr. 1928, 1).

One might wonder whether Mendelssohn’s oeuvre was as important to Koffler in the late 1920s and early 1930s (when he penned those articles) as it had been during his work on the doctoral dissertation. In his cyclic feature ‘A Survey of Music History’, which he authored in the same period, he does not even mention Mendelssohn in the instalment dedicated to Romantic music, though he discusses symphonic works from the second half of the century. In ‘A Survey…’, Mendelssohn is only mentioned once and only as the person who ‘discovered’ Bach.

Koffler wrote next to nothing about Chopin, though from his other texts we can learn that he considered Chopin’s output as eminently individual. Koffler mentions folk inspirations and claims that Chopin used them in the most artistic manner (but unfortunately he does not develop this thought).

Koffler assigns to Wagner a similarly essential role in the second half of the nineteenth century as to Beethoven in the first. He claims that ‘Wagner took up Beethoven’s tendency for expressing a philosophical idea in music’. Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg is, according to Koffler, ‘the best German comic opera’ after Le Nozze di Figaro (though the latter sets an Italian-language libretto). Koffler also recognises the importance of Wagner for later composers, arguing that ‘all the directions and all the divergent trends have their beginning in Wagner’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 9, 1 May 1928, 4–6). At the same time, Koffler writes unfavourably about the works of Johannes Brahms, criticising the latter for ‘blinkered imagination’ (ibid.), and expressing a preference for Anton Bruckner, who, he claims, sometimes surpassed Beethoven in his ‘thematic ideas’ even though he admittedly was ‘naïve’ or even ‘clumsy’ at times. However, Koffler praises the output of Gustav Mahler much more highly than that of Bruckner and Brahms.

Like many graduates of Vienna’s Institute of Musicology, Koffler frequently used the categories of ‘progress’ and ‘development’ in his texts on music history (after G. Adler, ‘Umfang, Methode und Ziel der Musikwissenschaft’, Vierteljahrsschrift für Musikwissenschaft, I, 1885). Guido Adler himself frequently took up the question of development (‘die Entwicklung der Kunst’) and progress in art in his writings concerning the organisation and aims of musicology. He considered it necessary to borrow methodology from natural science, and was actually convinced that there is something like ‘organic development’ in art. As Adler’s former student, Koffler partly adopts this line of thinking.

In his cycle ‘A Survey of Music History’, he writes of the ‘main lines of musical development’.

In his presentation of major medieval genres, he applies terminology associated with the then evolutionary theory, arguing that the early organum was ‘an attempt at primitive polyphony’, whereas parallel organum was ‘more artistic’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 5, 1 March 1927, 7–9). Koffler also describes the influence of Beethoven’s music on Wagner in terms of musical evolution. Most frequently he applies the notions of ‘evolution’ and ‘progress’ with reference to phenomena in contemporary music (for instance, the progress brought about in musical life by the radio).

Another term he uses is ‘revolution’, in the sense of a radical rejection of the earlier rules of composition. In this context, he points to Richard Strauss’s important contributions to overcoming the major-minor tonality. It was thanks to Strauss that ‘the relaxation of the sense and awareness of musical key was making further rapid progress’. According to Koffler, another ‘major figure in musical revolution’ was Ferrucio Busoni. Koffler views dodecaphony as a stage in the development of music and is convinced that the ongoing improvement of composition technique is ‘a historical principle’ (‘A Survey of Music History’, Muzyk Wojskowy 4, 15 Feb. 1928, 5–6).