Music Education and Pedagogy

Koffler assigns two functions to music education: 1) building general love of and knowledge about music, 2) professional training. The former category involves bringing up consumers of music (‘an environment characterised by a high level of musical culture’), whereas the latter aims at educating producers (composers and performers). In this way, Koffler raises the question of the ‘cultural function of music schools’ and their adaptation to the actual needs of the society (‘A Reform of Music Education’, Muzyk Wojskowy 24, 15 Dec. 1928, 5–6).

For would-be professional musicians, Koffler envisages two kinds of eight-year vocational schools: 1) music teacher training colleges, 2) instrumentalists’ schools. Such schools would only admit students with ‘outstanding talent’ who have graduated from primary school as well as passing medical and psychotechnical tests.

Completing one of these schools ought to result in qualifications ‘similar to those provided by academic studies’. Graduates could go on to study musicology at university, which means that the completion of a music school or college would be a requirement for all musicology candidates (ibid.). Koffler suggests that the existing music conservatories should be divided into general music schools, teacher training colleges, and instrumentalists’ schools, whereas other existing music schools and institutes ought to be converted into general music schools (a system he believes could work well for the next five decades).

In professional music school curricula, Koffler saw the need to include such general subjects as physics, mathematics, history, grammar, literature, foreign languages (German, French, and English), as well as aesthetics. Besides, learning three instruments should be obligatory (the main one, e.g. the piano, and two subsidiary ones – from the string and the wind family), plus singing and music theory. In teacher training colleges the set of subjects ought to be similar but taught from a pedagogical perspective. Instrumental training ought to be conducted in the form of alternating individual (one hour) and group lessons (half an hour of teaching to a class of ten). As the author of papers on teaching theory,

Koffler also refers to his own professional practice, admitting that teaching harmony to groups is hard due, among others, to students’ varying levels of intelligence, which made it impossible to adjust classes to individual abilities. By slightly modifying Hugo Riemann’s system, he develops his own method of teaching diatonic modulation, which he applies during classes at the conservatory. He considers it necessary, in particular, to reform theory syllabuses with regard to subject coordination.

Koffler emphasises that young students of composition classes in Poland should have the opportunity to get acquainted with the latest techniques and trends. He adds:

I do not recommend at all that they must write atonal, dodecaphonic, linear, athematic, or quartertone music. Nevertheless, they should know all these [techniques] in both theory and practice, from listening and from their own attempts.

(‘Avant-garde Music: A Bird’s-Eye View’, Muzyka 1/2, February 1935, 20–21).

He assigned these tasks to the ISCM (Polish Section) and the State Music Conservatoire in Warsaw.

Koffler dedicates much space to problems of music theory, for instance in the cycle ‘Problems of Music’ printed in Muzyk Wojskowy and in ‘Music and Composition Theory’, published in Orkiestra. In those texts, he discusses tone qualities, then such notions as ‘motif’ and ‘theme’ (illustrated with musical examples). He presents these problems in an accessible and condensed manner, without using difficult expert terminology. He also elucidates the meaning of harmony, using two radically different harmonisations of a well-known tune (‘Close by my garden yard…’) and his own Forty Polish Folksongs as examples of more varied harmonisation.

He explains how different harmonic treatment can completely alter the mood of the same melody, in which he goes beyond mere fundamentals. Concerning the history of harmony, he writes that Beethoven mastered and perfected ‘the use of sustained chord structures’, whereas Wagner developed this technique. He also notes that Schubert and Beethoven (and sometimes also Mozart) frequently broke the rules of harmony that were considered binding in their times. On another occasion, Koffler explains the notion of counterpoint and discusses the canon and imitation, using examples from his own folksong collection again (which thus, apart from its artistic merits, also proves very useful as a didactic tool).

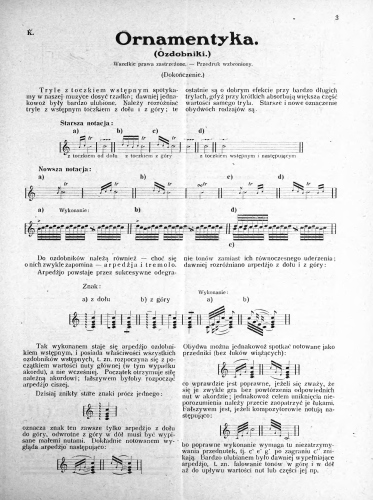

In another series of articles, he briefly characterises selected musical forms and genres (theme with variations, the suite, the sonata, the symphony, the oratorio, the cantata, and others) so that his audience may ‘fathom the beauty of the musical work’ during concerts (‘Problems of Music Continued’, Muzyk Wojskowy 11, 15 Dec. 1926, 6). Koffler then goes on to discuss the question of mood, referring to Eduard Hanslick’s view (expressed in The Beautiful in Music) that music need not always enhance textual meanings (Hanslick argues, for instance, that the aria ‘Che faro senza Euridice’ could equally set a text concerning the loss of Euridice as one about a reunion with her). Though contained in a then much opposed publication, in Koffler’s eyes Hanslick’s arguments deserve to be carefully studied. Koffler also wrote a series of articles titled ‘Ornamentation’, similarly illustrated with musical examples.